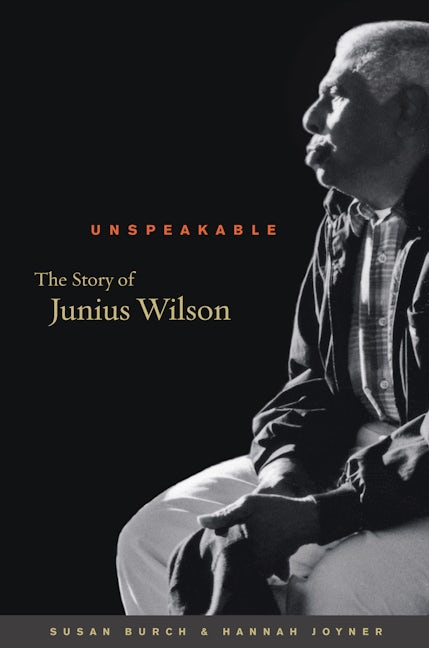

Unspeakable

The Story of Junius Wilson

By Susan Burch, Hannah Joyner

320 pp., 6.125 x 9.25, 19 illus., notes, bibl., index

-

E-book EPUB ISBN: 978-0-8078-8434-8

Published: November 2007 -

E-book PDF ISBN: 979-8-8908-8109-0

Published: November 2007 -

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-4696-2638-3

Published: November 2007

Buy this Book

Request exam/desk copyAuthor Q&A

Copyright(c) 2007 by the University of North Carolina Press. All rightsreserved.Susan Burch and Hannah Joyner, authors of

Q: Why is the story of Junius Wilson so remarkable? Tell us a little bit about him and hislife.

A: Junius Wilson was a deaf African-American born in North Carolina during the early years of the twentieth century. In 1925 he was accused of the attempted rape of a relative, found insane at a lunacy hearing, committed to the criminal ward of the State Hospital for the Colored Insane, and surgically castrated. Although he may have been falsely accused, was not found guilty, and was apparently never diagnosed as insane or retarded, Wilson was still an inmate at the hospital sixty-five years later. What happened to him once his advocates realized that he was completely misplaced is the subject of the final chapters of the book.

Wilson's story is "remarkable" in both its power and its particulars. But we should not dismiss his history as merely an isolated story, irrelevant to our understanding of the past more generally. Fundamentally, what happened to Wilson highlights the extent of what a society based on hierarchy and violence can do to its most vulnerable members. His story allows us to explore the depth of racism and disability discrimination, the intersection of Jim Crow policies and the eugenics movement, the impact of institutionalization, the changing meanings of mental health and social work across the twentieth century, and the unexpected sources of strength that emerged in the face of such a terrible tragedy.

Q: How did you first become aware of JuniusWilson?

A: Living in North Carolina in the 1990s, Hannah read about Wilson in local newspapers when his story first became public. In 2000, Susan was researching issues of diversity in America's deaf community and found the same articles Hannah had read. After initial research, it was clear to Susan that this story deserved greater attention. Wilson's advocates agreed, and generously provided access to private materials and memories. A shared interest in deaf history and African American history made our collaboration an obvious choice.

Q: Wilson attended a segregated institution, Raleigh's North Carolina School for the Colored Blind and Deaf. How was he educated? What kind of sign language was used at the school?

A: A: Wilson became part of a rich cultural community at the segregated deaf school, one that had its own form of sign language (called Raleigh signs) that deaf people – black or white - elsewhere did not know. At white schools for the deaf, in North Carolina and around the nation, students used American Sign Language.

Within the confines of the Raleigh school, the linguistic isolation was not a problem; Wilson and his peers shared a common language as well as a rich cultural identity. But when Wilson was kicked out of the school, he was unable to communicate clearly even with his relatives and neighbors back home. His linguistic isolation contributed to the wrenching experiences he endured.

Q: In what ways did Junius Wilson's racial background in the Jim Crow South allow the charges to be made against him?

A: Complicated issues of race, economics, family, and disability contributed to Wilson's initial arrest, but it appears that racial stereotypes also particularly affected his treatment in jail. The white jailer, judge, and jury likely saw the charge against Wilson - attempted rape of an African American woman - as proof of his genetic and racial inferiority. Like the image of the savage black rapist in Birth of a Nation, a movie that played to packed houses in Wilmington the week he was sentenced, Wilson seemed threatening. His inability to speak vocally (the result of his deafness) only emphasized his dangerousness. To the white observers at the courthouse, Wilson's staring, gesturing, and inarticulate speech were perceived not as deaf behaviors but as manifestations of his status as the 'black savage.'

Q: Was Junius Wilson illiterate as well as deaf? If so, does this explain why he was unable to defend himself in writing against the accusation of rape?

A: Literacy presented a surprisingly complicated issue in Wilson's story. Having attended a segregated deaf school for eight years, he had some literacy skills - although how much is unclear. Despite the fact that Wilson could in fact write at least basic information, the jailer, judge, and jury all apparently assumed that the deaf man was illiterate. They never provided paper or pen to the prisoner.

Language and racial barriers barred Wilson from a fair trial. No one who could understand Wilson played any part in his hearing. The assumptions of the jailors and judge combined with the accusation of attempted rape primarily defined the court proceedings. Wilson never stood trial for attempted rape nor was he ever found guilty of any crime. Instead, he was sent to the criminal ward of an insane asylum.

Q: What were Junius Wilson's relationships with staff members and with other patients at Cherry Hospital in Goldsboro, North Carolina like?

A: Many people assume that inmates in a psychiatric hospital don't share a sense of community, but Wilson's story shows a rich and diverse social history. He clearly had warm friendships with several staff members, playing pranks and running errands for them. He also interacted with other patients both in and out of the wards. They had a surprising amount of mobility around the campus of the institution. Wilson and other patients dug worms from the riverbanks to sell to various locals on their way to favorite fishing holes. From the money he made at this entrepreneurial activity, Wilson eventually bought himself bicycles, which allowed him to explore the area and get to know other citizens in the town of Goldsboro.

In addition, his relationship with another black deaf inmate from a similar background, James McNeil, points out that Wilson's story is not as singular as we might have wished. The ways in which Wilson, McNeil, and others provided support to each other and a sense of belonging reminds us that 'life on the inside' is as much a rich lived experience as life on the outside.

Q: When was it discovered that Junius Wilson was not insane?

A: Wilson was sentenced to an insane asylum in 1925, but evidence suggests that he never received a formal diagnosis of insanity. Following the trend to deinstitutionalize patient - inmates, staff at Cherry Hospital in the 1970s looked more closely at Wilson's case and doctors began to acknowledge that he was not mentally ill and almost certainly never had been. In spite of this fact, they chose to keep him another two decades in the locked wards of the institution.

Q: What was Junius Wilson's life like after he was finally freed?

A: Newspapers and advocates proclaimed that Wilson was "free at last" when he was transferred from the locked wards to a renovated cottage on the hospital grounds. There was much to celebrate. For example, he now had the ability to make more decisions about his daily schedule, including taking car trips away from the hospital grounds. Wilson also acquired more personal property to call his own. He loved to show off his hat collection to his visitors.

But moving to the cottage wasn't a complete victory. Hospital policies meant that Wilson couldn't have friends stay overnight. He was closely supervised at all times by the same staff members who had supervised him in the locked wards. For the first year in his cottage, he didn't even have a key to open his own front door. Some argued that this was no liberation, only another form of captivity, furnished with colonial style fixtures and a front porch. Junius Wilson's story is complex, demonstrating how difficult it is for even well-intentioned people to determine how to undo years of injustice.

Q: How did you research Unspeakable?

A: Researching this work was an adventure in itself. Wilson left behind precious few clues - like diaries or letters - that show how he saw his life and the world around him. We were fortunate to have access to his medical files, but privacy rights policies and hospital mandates made it especially difficult to find answers to some of the thorny questions Wilson's experiences raised about the lives of institutionalized people.

To learn about some of the events of Wilson's life, we were able to use court documents, public hospital records, newspapers, census records, and school reports. But the richest sources for us were the many interviews (some in sign language) that we conducted with friends, family, and others who knew Wilson. As outsiders to both the African American deaf community and to psychiatric hospitals, as well as other communities whose members we interviewed, we had to be especially sensitive in our approach to this deeply troubling history. The people we talked to were incredibly generous with their time and memories. It is clear that Wilson touched many lives and that many people wanted his story to be told.

Q: It is unusual for a biography to be co-written. Can you tell us about your experience working together?

A: Part of the gift of writing this work was doing it collaboratively. We have very different approaches to history, and different talents. Working together allowed us not only to bounce ideas off each other. Each of our strengths could come through. It also helped us learn new working styles that may influence future projects even when we're not working together.

Collaboration was especially helpful while writing this particular book. Because this story is fundamentally about isolation, we were mindful of the benefits of having another person just as intimately involved with the story with whom we could share our ideas and experiences as well as our emotional reactions.

Q: What do you hope will be the impact ofUnspeakable?

A: We as a society have a lot more to learn about the experiences of many of the people of this world.This work strives to shed light into some of these unexamined corners.African Americans from all walks of life remain in the margins of too many of our academic studies, as do deaf people of all walks of life. These two populations are both everywhere present and far too rarely seen. Institutionalized people are almost always left out of the story of our past. It is certainly our hope that this book will encourage others to investigate people who at first glance seem to be unknowable or invisible.

At the same time, we hope that Wilson's story will help us remember how complex history can be. Writing Unspeakable forced the two of us to move away from simple accusations or understandings. It would be easy, for instance, to place the blame for the injustices Wilson experienced on racist judges or hospital administrators. But in reality, the issues Wilson presented to participants in his story - participants from family members at the beginning of the twentieth century to social activists at its end - required them all to engage in intricate moral thinking. The truth of human motivations is far more complex than simple good and evil.

This is a story with many heroes: people who tried to do the right thing for Junius Wilson and for their families and communities. They all faced limitations on their heroism - limitations shaped by their times. Racism, disability discrimination, the power of institutions and institutionalization - as well as the effects of deeply entrenched poverty - chiseled into the options available to those who sought to act justly.

We hope that as readers explore how this story could happen, they will explore their own moral landscapes, and the moral landscape of this country. Fundamentally, Wilson's story is an American tale, and thus it is part of us all.