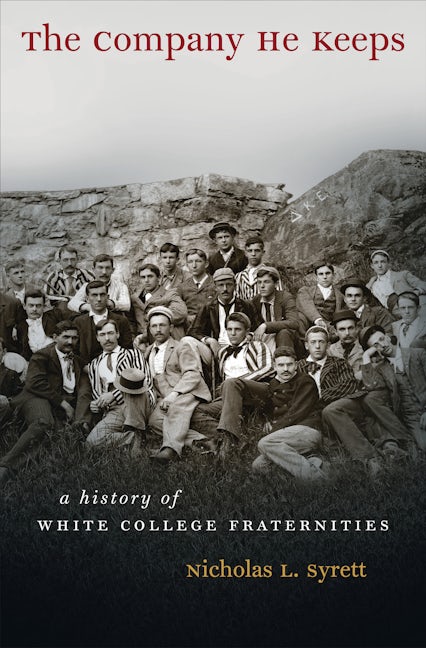

The Company He Keeps

A History of White College Fraternities

By Nicholas L. Syrett

432 pp., 6.125 x 9.25, 21 illus., notes, bibl.

-

Paperback ISBN: 978-0-8078-5931-5

Published: September 2011 -

E-book PDF ISBN: 979-8-8908-8126-7

Published: September 2011 -

E-book EPUB ISBN: 978-0-8078-8870-4

Published: September 2011

Buy this Book

Request exam/desk copyAuthor Q&A

Copyright(c) 2009 by the University of North Carolina Press.All rights reserved.

Nicholas L. Syrett, author of The Company He Keeps: A History of White College Fraternities, explores the bonds of brotherhood.

Q: What made you want to write The Company He Keeps? Have you ever belonged to a fraternity?

A: I have never belonged to a fraternity. Columbia, the school I attended as an undergrad in the mid '90s, did not have a particularly big Greek scene by the time I was there.

I was interested in writing about fraternities because I was fascinated by examples of groups of men behaving badly, gang rape in particular. It seemed to me that most of the men involved in incidents of gang rape that I read about probably would not have behaved as they did without the influence of others in the group. I ended up trying to answer the question "Where does this behavior come from?" by picking one group of men that participated in such incidents and tracing their history. That's how I settled on fraternities.

Q: Why do you think that this book is particularly timely?

A: It's timely for a number of reasons. The first is that an increasing number of schools of late have been considering either abolishing their Greek systems altogether or forcing fraternities and sororities to go coed. I hope my book can contribute to that conversation. The second reason is that the media continues to report every year on tragic cases of alcohol poisoning in fraternities, hazing gone wrong that results in injury or death, and the sexual assault of women at fraternity parties. My book explores where all of these phenomena come from. The third is that we continue to live in a society in which powerful white men are able to use their connections to forward their careers and interests. Some of those connections have been, and continue to be, forged in college fraternities.

Q: What role has homophobia played in the evolution of fraternities?

A: The short answer is that homophobia has played a very significant role. The longer answer is this: it played no role at all until the late nineteenth and early twentieth century when homosexuality itself became recognized as a sexual orientation that could be ascribed to certain people, people who were different from another category of people called heterosexuals. It began to play a role then -- and continues to do so now -- because fraternities are groups of single men who live together, and that looks suspicious, particularly when those groups of men select other men to join based in part upon their physical appearance, when they participate in nude hazing rituals with each other, and when they foster a friendship that appears remarkably affectionate to outsiders. Further, and perhaps even more importantly, fraternity men are very concerned with gaining prestige through demonstrating their masculinity, understood as being the antithesis of homosexuality for many people. One way to insist upon their masculinity is through ostracizing and mocking those they believe to be gay.

Q: Were you surprised by anything that you found in your research? Have any of your own impressions or assumptions changed in writing this book?

A: I was surprised by how intellectual fraternities were in their origins. Fraternity men of the early nineteenth century placed a premium on academic achievement and on literary and oratorical talent. I was also surprised by the role of alumni in fraternity culture, not so much because alumni go to events and think fondly of their college days, but because fraternities would have ceased to exist long ago without the devotion and interest of active alumni.

I also found occasional instances of gay men in fraternities from the early twentieth century onwards, and sometimes gay men who were remarkably active not just as undergraduates but also as alumni. Gay men in an exclusively male group might not be surprising at all, but it was to me, precisely because many fraternities are homophobic.

In terms of changed assumptions, I still think that when fraternity men (or any group of people at all) do bad things, they're still bad, but I've come to be more sympathetic to the reasons why so many men find these organizations so appealing. Fraternity membership wouldn't be for me, but it's clear that it serves real needs for many men, and those needs themselves are important and should be recognized.

Q: What do you think are the key differences in fraternity culture of the nineteenth century and now?

A: The first difference is the intellectual origins that I mentioned above, the conceived link between manliness and scholarship in the era before the Civil War. That changed by the late nineteenth century, when performance in academics as a measure of success was replaced by performance in sports. It's remained that way at least through the post-WWII period and, in many fraternities, to the present day.

The second big difference is in regards to women. In twentieth- and twenty-first century fraternity life, there has been a huge emphasis placed upon dating and sexual success that simply did not exist in the early nineteenth century, at least not in the form we see now. To a certain degree that is true for all American men, but there is no question that fraternity men have taken the emphasis upon active heterosexuality to great lengths.

Q: What would you say was the big turning point in the history of fraternities?

A: Two turning points seem particularly significant. The first is fraternities' decision in the late nineteenth century to exclude all but white Protestants. This was a result of the arrival in greater numbers of people of color, Jews, and Catholics at colleges. Traditionally white college fraternities opted to remain exactly that, and those who were excluded formed their own Greek-letter organizations as a result.

The second turning point is the decade of the 1920s when dating was born and increasing numbers of schools went coed. Men also began to have sex in increasing numbers with working class women, and they used this as a measure of their masculinity and popularity as well.

Q: How do you see fraternities as a mirror for the culture and times? Are there ways in which they have developed independent of society?

A: Fraternities -- and the schools at which they make their homes -- have changed as the United States has changed and, if anything, they are a heightened and magnified example of the culture. They became pre-professional as the middle class did so. They excluded non-whites and non-Protestants as the white middle class also did so. They dated and pursued sex in the 1920s and again after the sexual revolution of the 1960s as the rest of the country did as well.

Yet fraternities have also developed apart from society in a number of ways. Because they have been populated by college students, who are at a transitional stage in their lives and are not occupied by families or jobs, fraternity members have been free to devote a good bit of their time to their organizations. Even more importantly, when they have misbehaved they have rarely had to face the consequences of the criminal justice system. Colleges and universities, always protective of their own reputations, have often shielded fraternity men and punished them through collegiate judicial systems, if they did so at all.

Q: You looked at fraternities in a wide range of geography, from Dartmouth to Duke. Did you see regional differences in fraternity culture?

A: There are two primary ways in which geography has had an impact. Because of the kinds of people who attended college in the pre-Civil War years in different regions, fraternities were much less popular in the South than they were in the North and Midwest. They would only arrive in the West as white Americans moved further westward after the Civil War.

The other main difference also relates to the South and has to do with race. When fraternities began to integrate after World War II and in the wake of the Civil Rights movement, Southern fraternities were (and some still are) much more reluctant to do so and have clung to racial exclusivity much longer.

In many other ways, however, region did not make as much difference as I had expected it would. This is, in part, because most fraternities are national organizations bound to each other by shared constitutions, regulations, and central offices.

Q: Do you think that university regulation of fraternities, such as banning hazing or revoking housing privileges, has had a tangible affect on fraternity culture?

A: There's no question that some schools have been more successful than others at "taming" their fraternities. These may well be schools that enroll a student body less wedded to fraternity culture to begin with. But some of it may have to do with the degree to which the school is committed to whatever policy -- particularly anti-hazing policies -- that it implements.

I think the most successful moves have been to dissolve individual chapters, admittedly an extreme step. This may well be winning the battle but not the war, however, as the members can certainly join other organizations. Some schools have also met with success by mandating that their fraternities admit women. In very real ways, however, these organizations cease to be fraternities in the traditional sense. Another important distinction is whether or not the administration has control over the fraternity houses: are they on campus or off? Are they owned by the college or by the fraternities? The answers to those questions have much to say about what kind of regulation the colleges can impose and whether it will be successful.

Q: It seems as though the closer to the present your research gets, the more disturbing fraternity behavior becomes. What needs to happen for this trend to change?

A: I think that fraternity men need to become more comfortable with the affection, intimacy and friendship that they get from being in fraternities without fearing that others will think them gay because of it. This would go a long way toward reducing homophobia among fraternity men.

I also think that fraternity men need to stop measuring their masculinity and their esteem based on their sexual success with women. Fraternity men need to be able to take women, aside from just their mothers and sisters, seriously. They need to understand that women don't exist simply for their own pleasure but as thinking human beings with their own agendas.

By the same token, I think that women and college students in general need to stop kowtowing to fraternity men. So long as fraternities are allowed to get away with their antics because they are popular, desired, and envied, they will continue to do so.

College administrations need to be more vigilant in cracking down on fraternities when they misbehave. No more second chances and no more bowing to alumni pressure. They also need to make sure that there are other opportunities for socializing on college campuses, so that fraternities and sororities don't maintain such a strong hold on these activities. If there were more social options, and they were attractive, students would take advantage of them and fraternities wouldn't control the social scene at so many schools.

Lowering the drinking age to 18 would also help matters because then students could go off campus, to bars and restaurants, for alcohol instead of relying upon fraternity parties, which consistently break the law by serving minors. Making alcohol available elsewhere would significantly lower the appeal of fraternities.

Q: You state in your introduction that, "Not all fraternities are as bad as this book makes them out to be." How would you characterize these fraternities? Are they exceptions to the rule?

A: Some fraternities have very self-consciously adopted different ways of defining themselves. The most obvious examples are those that have different memberships: fraternities for people of color, for instance, that emphasize their respective cultures. Or gay fraternities. Multicultural fraternities were formed at the same time that scandals were erupting around discrimination over all-white fraternities, and they very consciously embraced racial diversity. Coed fraternities largely eschew an emphasis upon masculine sexual achievement because their male members relate to women as equals and as members.

Still others are less concerned with sports or sexual conquest. Whether or not this is by conscious choice of the organization (as it is sometimes) or by dint of who actually ends up joining is another matter. The bottom line is that those fraternities who most emphasize racial diversity, academic achievement, tolerance and acceptance of gay members, or opposition to alcohol abuse are almost never the most popular on a college campus.

Q: What do you think are the clear benefits of a fraternity for brothers? For a university?

A: The biggest benefit for fraternity brothers is friendship or "brotherhood." This is particularly important for students who attend large and impersonal schools where they might not know anyone upon arrival. Joining a fraternity provides instant and potentially very loyal friendship. The other benefits include prestige, a place to live, access to parties and the women who attend them, and the chance to partake of connections that might afford advantages, particularly in employment, once one has graduated from college.

The benefits for colleges are twofold: fraternities provide housing and they provide a social life for fraternity members, thereby freeing the college from assuming those responsibilities.