The Provincials

A Personal History of Jews in the South

By Eli N. Evans

440 pp., 5.5 x 8.5, 32 illus.

-

Paperback ISBN: 978-0-8078-5623-9

Published: February 2005 -

E-book EPUB ISBN: 978-0-8078-7634-3

Published: February 2005 -

E-book PDF ISBN: 979-8-8908-8034-5

Published: February 2005

Buy this Book

Request exam/desk copyAuthor Q&A

Copyright (c) 2005 by the University of North Carolina Press. All rights reserved.Book News | Family Album | Recipes from the Book

A Conversation with Eli N. Evans

Author of The Provincials: A Personal History of Jews in the South

Q: THE PROVINCIALS is considered a classic, and has been continuously in print since 1973. Why is this the right time for a new edition?

A: We are in the midst of a year-long celebration that marks the 350th year of Jews coming to America. All over the country, this is a year of renewal, a period of reflection and self-examination, and a new resolve for the future of the most free and successful Jewish community in history. It was so fitting that the oldest university press in the South also embraced the idea of a regional celebration of Southern Jewish history. The story of Jews in the South is not widely known or appreciated, but is essential to understanding the American Jewish experience, and the special ways in which Jews in the South have contributed to the history of America and what America and the South have given back to the Jews.

Q: The book now includes family photographs, as well as portraits of notable Jewish figures in Southern history. Why did you decide to include them?

A: When Kate Torrey, the director of the UNC Press, first told me the Press wanted to reissue the book to help mark the celebration, her plan was to publish the book in a dramatic way, with a beautiful new cover, sixteen pages of photographs, and in hardback and paperback simultaneously. I had always hoped to have a version of the book with photos to reflect the conceptual rhythm of the book—the historical and the personal. I wanted an edition that would reflect the visual imagery of the story and respond to the empathy of readers curious to know the personalities in the autobiographical chapters as well as the grand characters I encountered in my research and travels. And I gave a great deal of thought to the selection of images and to the captions for the photos to tell the story of the book.

Q: How did the initial publication of THEPROVINCIALS surprise you? Do you still hear from readers?

A: In the end, readers keep a book alive. This one was not an instant success, but grew over time as it was reviewed and word of mouth stirred up interest. It flourished as the population of the Jewish South expanded. Readers began to share it with friends and family; neighbors gave it to newcomers as a kind of guidebook to the Southern Jewish experience—maybe because I even put in some recipes—for Kosher Grits and Atlanta Brisket.

Once, a man who had moved from New York to Hickory, North Carolina, came up to me at a book fair on Fifth Avenue with his own well-read copy and asked me to sign it. When I asked him where he got it, he said "It came on the welcome wagon with the grits and the football tickets."

I still get mail and hear directly from readers. Many of the letters echo a theme—that the book caused them to reconsider their grandfather's struggles as a peddler and small store owner, transforming their past into an adventure in courage to be celebrated, instead of an impoverished past to be forgotten. The philosopher Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel once said "it is not enough to be a story teller; one has to pray for good listeners." I have been blessed with good listeners.

Q: Are you hoping to reach a new audience with this new edition? Where do you think the book will find the most readers?

A: For one thing, the number of Jews in the South has tripled in the last thirty years, but I believe there will be a national audience of all faiths because of the natural interest from the 350th celebration. And I think there will be a great deal of interest from general readers who want to understand the South and from anyone interested in the intricate relationships and interplay of different religions in the South, both for children and adults.

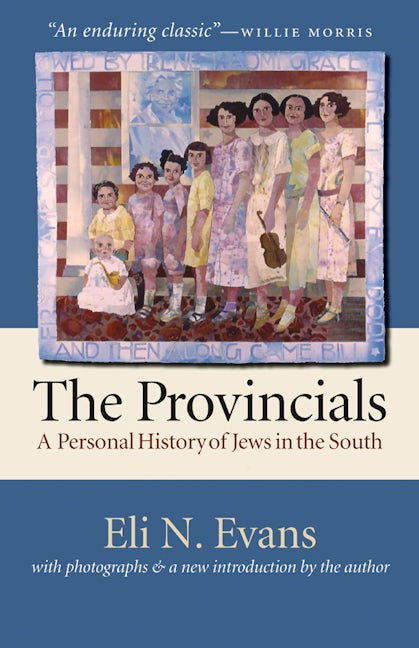

Q: Where did the painting on the cover come from and what does it represent?

A: It is a painting of my mother's family, the Nachamson family of Kinston and Durham, North Carolina. Actually, it is not a painting but a collage made from cut paper which the artist, Marilyn Cohen, entitled Jennie's Almost All-Girl Band. The "painting" portrays the family's eight consecutive daughters and then a son (my mother, Sara, at the right, was the oldest) against a backdrop of the American flag and the image of my grandmother, Jennie, whose 1905 marriage to Eli Nachamson created a family tree of ninety-seven souls. The artist selected our family to represent North Carolina as part of a project of fifty paintings entitled "Where Did They Go When They Came to America" which toured a number of museums around the country several years ago. It is a perfect cover both for the 350th, and as a reflection of Jennie's pride in her family and our gratitude to America. The UNC Press has published what really serves as a collector's edition, the version of the book I have always dreamed of.

Q: What do you think will surprise readers most as they read your book?

A: That the book is multi-layered, operating on many different levels at once and has fresh insights about growing up Jewish in the South that are instructive about America.

This new edition is a homecoming for me because I was raised in Durham and graduated from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Much of the autobiographical material in the book came out of a diary I began in college and the interviews I did with my parents and the rest of my large family. I also traveled 7,000 miles over a two-year period interviewing Jews as well as non-Jews about their stories, impressions and attitudes. The book blends autobiography with history and journalism, and this new edition gave me the opportunity to update parts of the book.

Q: What makes the book relevant to today's world?

A: Jews are different and have always been "the other" in almost every country they have lived in. In the South, they stand apart from the overwhelming religious presence that dominates Southern culture. In a twenty-first century American political environment, where religious beliefs, values and practices define the cultural divide between sections of the country, the experience of growing up Jewish in the Bible Belt can offer important insights into the soul of the South.

Yet, the Jews of the South were not insular, but participated ardently in civic life. They developed a unique Southern Jewish consciousness and understood that a better community for everyone was a better community for Jews. In community after community, all over the South, Jews have been elected to office, served on boards of museums, libraries, schools, and civic organizations. Looking at the South through the prism of Jews in the South, and through the eyes of the Jewish Southerners who live and lived there, can teach us a great deal about both America and the South today and the importance of religious pluralism as a bedrock American value.

Q: What are the roots of this modern relevance?

A: Jews have always an intimate presence entwined with the South, from the very earliest chapters of Southern history, a part of its passions, and its narrative. Most people are astonished that in 1800, there were more Jews in Charleston than in any other city in America. Jews were attracted to Charleston by its growth and opportunity as a port city, and by its spirit, symbolized by the state constitution, which had been written by John Locke. Charleston became the first government in the new world to grant Jews the freedom to vote, own land, run for office, go into any profession, go into business with non-Jews, join the militia, leave money and property to heirs. All those rights, which were denied to Jews in so many other countries, meant opportunity. The news spread all over the world that "America is free," the first country to offer such a "golden door."

It was a Jewish fantasy even to imagine such a place, and Jews who came to Charleston were welcomed by the ruling fathers. Of course, there was a pragmatic reason for the reception as well. Jews had contacts in England, Belgium, and Holland and for the new colony, their arrival meant trade, art and culture as well. That, too, was new. They were needed.

Q: Why should the public be interested in the minor history of Jews in the South compared to the major story in the big Northern cities?

A: The easy answer is that they are part of the American story (and not so small anymore, with 1.2 million people). But there is a deeper, more important reason. Historians and commentators know that Jews are shaped by the ethos they grow up in. In the American ethos, the air we breathe radiates with religious liberty. In the period just after the American Revolution, Washington and Jefferson campaigned for the Bill of Rights which included freedom of religion. America was not a "Christian nation," though we still debate the issue today. It was a haven for all faiths because religious liberty was in the DNA of the American dream. Jews were a test fro the nation's commitment to this revolutionary idea of religious freedom which has shaped the American Jewish experience.

For the South, the role of Jews in its history is important because their presence demanded, for the most part, a pluralistic attitude. You cannot understand America without understanding the South. And many readers have told me how much they learned about the South from reading about it from a Jewish perspective.

Q: But what about anti-Semitism, the Klan,and the racism they encountered later?

A: Unfortunately, anti-Semitism is the most extensively written about aspect in much of the literature about Jewish life in the South. But the history of Jews in the South lies not in cross burnings, bombing, acts of overt anti-Semitism and violence. It is a story animated by hope, reflected in the indomitable spirit of immigrants who worked for pennies to bring over their families in the faith they could build a life in America. Jews have prospered in the South despite their religious differences and the spasms of violence and demagoguery that mar its history.

I maintain that one of the reasons lies in an emotional and psychological reality at work in the psyche of the Christian community. I call it a "reverence for Jews," and it has not been deeply explored or understood. To many Southerners, Jews were the chosen people, and had a Biblical dimension to them. One could be suspicious of the Jews you did not know, but not about the Jews who you came to know and were your neighbors. In their hometowns in the American South, Jews were mostly welcomed by the places they chose to settle, and they prospered and became eager contributors to society.

Q: What are the future prospects for Jews inthe South?

A: Overall, the Jewish population in the South has tripled in size since I first started writing about it in 1970—from 382,000 to an estimated 1,200,000 in 2004. Atlanta is now one of the fastest - growing Jewish communities in America, growing from 16,000 and three congregations when I first wrote about it in 1969 to well over 100,000 and thirty-seven congregations today. Austin, Texas has grown from 500 Jews when I was first writing about it to 15,000 to 18,000 today, mainly because of the arrival of Dell Computer and other high tech firms and the growth of the University of Texas. The Research Triangle of the Durham-Chapel Hill-Raleigh area has quadrupled in thelast twenty years and Charlotte is well on its way to becoming the Atlanta of the twenty-first century. The Jacksonville-Tampa-Orlando areais also growing dramatically.

The history of Jews in the South is now centuries old, but the story is still being written. Southern Jews of today are building communities with a new sense of self-confidence, pride and self esteem in a "NewSouth" that, after a century of social change, has wrestled with its demons and now faces a new dawn in a more pluralistic America.