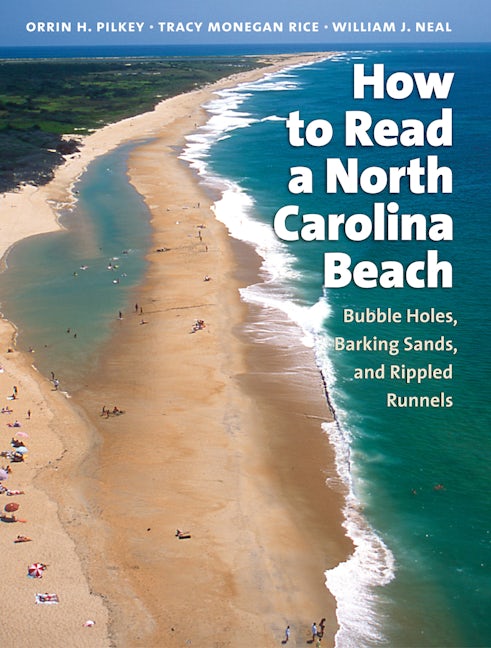

How to Read a North Carolina Beach

Bubble Holes, Barking Sands, and Rippled Runnels

By Orrin H. Pilkey, Tracy Monegan Rice, William J. Neal

180 pp., 6 x 8, 8 color and 79 b&w photos, 10 illus., 4 tables, 2 maps, bibl., index

-

Paperback ISBN: 978-0-8078-5510-2

Published: March 2004 -

E-book EPUB ISBN: 978-1-4696-1967-5

Published: March 2004 -

E-book PDF ISBN: 979-8-8908-7827-4

Published: March 2004

Buy this Book

Request exam/desk copyAuthor Q&A

Copyright (c) 2004 by the University of North Carolina Press. All rights reserved.A conversation with Orrin H. Pilkey, co-author of

Q: Your working title for this book was "Riddles of the Sand." Why?

A: Actually, our working title was"Everything You Needed to Know about Beaches except Seashells." Thereare thousands of books about seashells, but none about bubbly andbarking sand. "Riddles of the Sand" refers to the fact that there areall kinds of features on the surface of beaches. For those withcuriosity, they are riddles that need to be solved, and when you solvethem you have achieved a rapport with the beach.

Q: What makes this book different from other popular beach guides?

A: There are virtually no booksfor the public that cover this aspect of beaches. It's a shame that mostpeople just walk over all the ripple marks and all the rest as they lookfor shells and birds. We aim to stamp out bird watching and shellhunting (only kidding). The next generation of beach goers–if everythinggoes right–will spend their time examining the surface of beaches,finding out the history of the beach, and what processes have been atwork in recent days. One could write books about what's on a singlebeach and what the beach has to tell us, and, of course, that's what wedid.

Q: How can beach goers get the most from this book? Did you have an intended audience in mind?

A: I think beach goers should takethe book with them to the beach. Don't worry about it getting sandy orwet. Compare the photos and descriptions in the book with what you cansee on the beach. If you are going to be around for a while, trywatching the beach in the surf zone as the water level goes up or downwith the tides and see the various features form. Put on a mask andwatch them form in deeper water but be careful of the surf. When a stormcomes by check the beach out just before and just after the storm.

Q: You're a well-known marine geologist and environmentalist. What sparked your initial interest in beaches?

A: Although I started out as adeep sea sedimentologist working in 5000 meters of water, I have alwaysbeen interested in beaches. I have been taking students to beaches for40 years and even in my deep sea days I loved it. The students alwaysask questions and over the years I have learned what it is that catchesthe curiosity of the occasional beach visitor. Student questions havecaused me to do a lot of reading and to make a lot of fieldobservations. A lot of things in the book resulted from studentcuriosity.

Q: What do beaches have in common with other kinds of sedimentary formations?

A: Beaches have the potential toform sandstone formations, although such formations are less common inthe rock record than sandstones formed by sand deposits from thecontinental shelf, rivers, deltas, and even deep-sea deposits. Beachdeposits are less likely to be preserved because of the high–energy,wave environment in which they form. Beaches share a property with othersand deposits that geologists call "facies." That is, structures likeripple marks, blisters, types of bedding, and the kinds of fossils thatare unique to each environment. By studying modern beach deposits, wecan determine the features that differentiate beach sandstones fromthose of rivers, deltas, and other environments in the ancient record.

Q: What kinds of clues to beach formation are offered by shells?

A: Shells tell us something aboutthe history of a beach. For example, if a beach has a lot of blackshells, and particularly black oyster shells, you know that the barrierisland has migrated over an old lagoon. Black shells and oysters are asure sign of a nearby deposit of sand from an old lagoon seaward of thebeach. As the island moves over the old lagoon the deposit surfacesagain in shallow water on the inner continental shelf where waves breakit up and the material eventually moves to the beach.

Q: What is a rogue wave and is there reason to fear them?

A: A rogue wave is formed at seawhen waves coming from several directions are briefly combined to form asingle giant wave. Usually the rogue wave will be around for a fewminutes as it breaks up into its component smaller waves. A number ofrogue waves have been reported well out to sea by ships off CapeHatteras. A few years back, a rogue wave came ashore in the middle ofthe night on a beach on the east coast of Florida but luckily, no onewas hurt. They are a very rare feature in shallow water and I wouldn'tlose any sleep worrying about them.

Q: Why are sharks' teeth common on North Carolina's beaches despite the relative rareness of sharks off our state's shores?

A: The sharks teeth in NorthCarolina beach sand are fossils, probably 10 million years old or older.They come from ancient limestone on the adjacent continental shelf andare swept on shore by the waves. Their black color is due to the factthat their original composition was changed to a phosphate mineral whilethe teeth were residing in the rocks.

Q: Why does the quantity of shells on a beach change from day to day?

A: A few years back I took half ofa class to a beach on Shackleford Banks and we noted large numbers ofconch shells. The very next day I took the other half of the class tothe same beach and there was nary a conch shell in sight. It was astartling example of the role of waves in controlling what shells are ona beach. The conch shells were rolled back into deeper water because ofa small storm that came by, but I'm sure they were back on the beach in a few days or weeks.

Q: Can readers apply what they've learned from How to Read a North CarolinaBeach to other seashores?

A: We could just as well havetitled the book "How to Read a Sandy Beach." What we speak of is foundon the beaches of Japan, Mozambique, Argentina, and India. However, wewould have to write a different book for the cliffed shoreline ofCalifornia, the rocky, gravelly beaches of Maine, or for the frozenbeaches of the north slope of Alaska.

Q: What kinds of misconceptions do people have about North Carolina beaches(or beaches in general)?

A: The most importantmisconception is that beaches are fragile—far from it. As long aswe don't drive on beaches or build seawalls along them, they will go onforever and ever.

Q: In your opinion, what is the greatest threat to North Carolina beaches?

A: We have met the enemy and he isus. Beaches have no natural enemies. Storms may move them about a bit,but they will always be there. As the sea level rises, they will changetheir location, but they'll never go away. We can destroy beachescompletely however by building walls and we can also damage them bypumping up lousy sand for nourished beaches.

Q: How can one improve one's chances of hearing sand bark, sing, or squeak?

A: Just be observant, read what wesaid were the ideal conditions for barking, and do a lot of walking(shuffling) on the upper beach. You'll hear barking before long on mostbeaches.